WILLIAM LEE, INVENTOR OF THE KNITTING FRAME

In 1583 William Lee returned from his studies at the University of Cambridge to become the local priest in Calverton, England. Elizabeth I (1568-1603) had recently issued a ruling that her people should always wear a knitted cap. Lee recorded that "knitters were the only means of producing such garments but it took so long to finish this article. I began to think. I watched my mother and my sisters sitting in the evening twilight plying their needles. If garments were made by two needles and one line of thread, why not several needles to take up the thread?"

This momentous thought was the beginning of the mechanization of textile production. Lee became obsessed with making a machine that would free people from endless hand-knitting. He recalled, "My duties to Church and family I began to neglect. The idea of my machine and the creating of it age into my heart and brain."

Finally, in 1589, his "stocking frame" knitting machine was ready. He traveled to London with excitement to seek an interview with Elizabeth I to show her how useful the machine would be and to ask her for a patent that would stop other people from copying the design. He rented a building to set the machine up and, with the help of his local member of Parliament Richard Parkyns, met Henry Carey Lord Hunsdon, a member of the Queen's Privy Council. Carey arranged for Queen Elizabeth to come see the machine, but her reaction was devastating. She refused to grant Lee a patent, instead observing, "thou aimest high, Master Lee. Consider thou what the invention could do to my poor subjects. It would assuredly bring to them ruin by depriving them of employment; thus making them beggars." Crushed Lee moved to France to try his luck there; when he failed there , too, he returned to England, where he asked James I (1603-1625), Elizabeth's successor, for a patent. James I also refused, on the same grounds as Elizabeth. both feared that the mechanization of of stocking production would be politically destabilizing. It would throw people out of work, create unemployment and political instability, ad threaten royal power. the stocking frame was an innovation that promised huge productivity increases, but it also promised creative destruction (Daron Acemoglue and James A. Robinson: Why Nations Fail, (pp. 182-183))

Second Account:

William Lee is first mentioned as the inventor of the knitting frame in a partnership agreement between himself and a George Brooke on 6 June 1600. Lee was to provide the technology and Brooke the finance to produce the machine commercially. Brooke was to invest in the project and the first in profits were to go to Lee, all further profits would be shared between the two partners for a period of 22 years. Unfortunately events conspired against Lee when in 1603 Brooke was arrested on a charge of treason and executed.

Over the next ten years Lee continued to seek backing to develop his invention in London but with little apparent success. There has been much speculation as to the reasons for his failure: a knitting machine may have been seen as a challenge to the vested interests of the London weaving industry, Lee may lacked the required business acumen, or possibly converting his ideas into a practical machine was proving difficult.

Advisors to the Queen were also said to be unimpressed and questioned the quality of the product. Lee was refused a patent. Their rejection may have also been political, fearing the possibility social unrest following large numbers of hand knitters being added to an already growing pool of people without work.

In-spite of the setbacks Lee remained convinced of the merits of his invention, and eventually moved his operation to Rouen in France where he found a more receptive audience. Lee was granted a patent by the King of France, and on 16 February 1612 signed a contract with a Pierre de Caux to provide knitting machines for the manufacture of silk and wool stockings. He also agreed to provide English operators for the machines and to train French apprentices. A manufacturing base for the production of knitting machines was also to be established in Rouen.

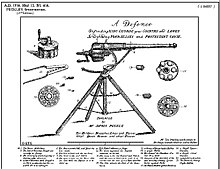

In its fully developed form the knitting frame could sow 600 stitches per minute using a hooked needle of a design, which has remained a key component of knitting machines to the present day.

The last known reference to Lee is in a 1615 French legal document, at this time he was still living in Rouen and is referred to as and English gentleman whose occupation was the knitting of stockings. Some accounts refer to Lee having a brother who traveled with him to France, and later after his death, returned to England to set up the first workshop in London using knitting frames to produce silk stockings for the wealthy.

The invention of the knitting frame was a remarkable achievement for its day and pre-dated the true industrial revolution by almost 200 years. By hand, it took two working days to knit a single stocking, but using a knitting frame this could achieved in one in one twelfth of the time.

Sources:

The History of Patents - video

The History of Patents

The History of Patents to the 20th Century

Patents, the Foundation of Innovation

Although there is some evidence that some form of patent rights was recognized in Ancient Greece in the Greek city of Sybaris,[8][9] the first statutory patent system is generally regarded to be the Venetian Patent Statute of 1450. Patents were systematically granted in Venice as of 1450, where they issued a decree by which new and inventive devices had to be communicated to the Republic in order to obtain legal protection against potential infringers. The period of protection was 10 years.[10] These were mostly in the field of glass making. As Venetians emigrated, they sought similar patent protection in their new homes. This led to the diffusion of patent systems to other countries.[11]

The English patent system evolved from its early medieval origins into the first modern patent system that recognised intellectual property in order to stimulate invention; this was the crucial legal foundation upon which the Industrial Revolution could emerge and flourish.[12] By the 16th century, the English Crown would habitually abuse the granting of letters patent for monopolies.[13] After public outcry, King James I of England (VI of Scotland) was forced to revoke all existing monopolies and declare that they were only to be used for “projects of new invention”. This was incorporated into the Statute of Monopolies (1624) in which Parliament restricted the Crown’s power explicitly so that the King could only issue letters patent to the inventors or introducers of original inventions for a fixed number of years. The Statute became the foundation for later developments in patent law in England and elsewhere.

Important developments in patent law emerged during the 18th century through a slow process of judicial interpretation of the law. During the reign of Queen Anne, patent applications were required to supply a complete specification of the principles of operation of the invention for public access.[14] Legal battles around the 1796 patent taken out by James Watt for his steam engine, established the principles that patents could be issued for improvements of an already existing machine and that ideas or principles without specific practical application could also legally be patented.[15] Influenced by the philosophy of John Locke, the granting of patents began to be viewed as a form of intellectual property right, rather than simply the obtaining of economic privilege.

The English legal system became the foundation for patent law in countries with a common law heritage, including the United States, New Zealand and Australia. In the Thirteen Colonies, inventors could obtain patents through petition to a given colony’s legislature. In 1641, Samuel Winslow was granted the first patent in North America by the Massachusetts General Court for a new process for making salt.[16]

The modern French patent system was created during the Revolution in 1791. Patents were granted without examination since inventor’s right was considered as a natural one. Patent costs were very high (from 500 to 1,500 francs). Importation patents protected new devices coming from foreign countries. The patent law was revised in 1844 – patent cost was lowered and importation patents were abolished.

The first Patent Act of the U.S. Congress was passed on April 10, 1790, titled “An Act to promote the progress of useful Arts”.[18] The first patent was granted on July 31, 1790 to Samuel Hopkins for a method of producing potash (potassium carbonate).

Six significant moments in patent history

(This article was produced independently of Reuters News. It was created by the public relations department of Thomson Reuters Intellectual Property & Science division, and Reuters Brand Content Solutions.)The concept of patenting reaches back to ancient times, though there is some dispute over which innovator succeeded as the first intellectual-property pioneer. As early as 600 B.C., according to British intellectual property expert Robin Jacob, a patent was documented for “some kind of newfangled loaf” of bread.

Here’s a look at some historical milestones in the long history of patents:

ANCIENT INNOVATION AND FIRST PATENTS

Some historians date the first industrial patent filing back to 1421, attributing it to Filippo Brunelleschi, a Florence architect who developed a crane system for shipping and transporting marble from the Carrara mountains.

John of Utynam, a Flemish glassmaker, is considered the first person on record to have been awarded an English patent in 1449. Granted by King Henry VI, the exclusive rights gave John a 20-year monopoly on producing stained glass — a technique that was until that point unknown in England.

THE VENETIAN ACT OF 1474

By 1474, the Venetian Senate set up the first patent law articulating the concept of intellectual property and enshrining the importance of protecting inventors’ rights. The Venetian Act is cited as the foundation for modern international patent statutes and was a “huge breakthrough in Renaissance Venice,” said Craig Nard, director of the Intellectual Property Center at Ohio’s Case Western Reserve University.

“Everything we hold dear as sort of fundamental principles in today’s patent system can be found in that Venetian statute,” he said.

THE 1624 BRITISH STATUTE OF MONOPOLIES

During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and her successor, King James I, the royal court bestowed patents on well-established techniques or commodities (vinegar and playing cards, for instance) to favored courtiers, Nard said. This patronage raised some civil unrest, and administration of patents was transferred to common law courts.

“In 1624, parliament had enough of this abuse of practice,” he said. “So they enacted this Statute of Monopolies in Section 6 that said we’re OK with patents, but you have to grant them on inventions that are actually novel.”

The rollback of the Crown’s powers governed English patent law for more than two centuries and forms the foundation of the modern British patent system, as well as a model for U.S. Patent Law.

FIRST PATENT ACT OF THE U.S. IN 1790

The 1787 U.S. Constitution laid the groundwork for granting patent rights to inventors in Article One, section 8, clause 8.

“Our founders actually contemplated intellectual property, patents and copyrights, which I think was remarkable,” Nard said.

A year after the constitution was ratified came America’s first Patent Act, on April 10, 1790.

More major reform came with the Patent Act of 1952, which further strengthened the patent system by introducing “non-obviousness” of procedure or product as a requirement for obtaining a patent.

“The 1952 act provided a greater menu of vehicles to show infringement,” said Nard, who described the revised act as the “backbone” of modern patent laws.

DIAMOND V. CHAKRABARTY IN 1980

The 1980 decision in the case of Diamond v. Chakrabarty answers the question of whether living organisms could be patented, a ruling that Nard credited for launching the biotech industry.

The dispute arose when microbiologist Anand Chakrabarty, who was working for General Electric, filed a patent application for a genetically engineered bacterium capable of breaking down crude oil.

“It was controversial because the patent examiner denied the bacteria under the patent code because he said life is not patentable,” Nard explained.

The case was appealed and reversed, and then brought to the Supreme Court, where Chief Justice Warren Burger held that Chakrabarty’s bacteria was indeed patentable.

“For the Chief Justice, the issue was not living or non-living. The issue was whether Dr. Chakrabarty’s invention did indeed have markedly different characteristics than that which occurred naturally. And indeed, it was not something you would find in nature,” Nard said. “Right there, the court gave a huge boost, as you can imagine, to the biotech industry.”

2012: CHINA’S PATENT DOMINANCE

Some 1.98 million patent applications were filed in 2012 at the world’s five largest patent offices, with China filing 526,412 applications, surpassing the U.S.’s 503,582 patents.

China’s State Intellectual Property Office overtook the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office as the largest patent office in the world, an outcome forecast in 2005 by Thomson Reuters researchers.

- tc-thumb-fld: a:2:{s:9:"_thumb_id";s:3:"314";s:11:"_thumb_type";s:5:"thumb";}

- layout_key:

- post_slider_check_key: 0